While the number of employees earning the minimum wage has increased across Europe over the last decade, spurred by significant minimum wage hikes, a clear gender divide emerges, with minimum wage earners more likely to be women. Minimum wage earners are also more likely to live in materially deprived households.

Despite the progress in statutory minimum wages across the many EU Member States over the last decade, the situation highlights important divides.

Higher minimum wages, more minimum wage earners

In 2019, around 7% of employees in the EU were statutory minimum wage earners - that is, earning up to 10% above or below the minimum wage rate in each Member State. Across countries, this rate ranges from 10 to 15% in several central and eastern European Member States (Romania, Poland, Bulgaria, and Lithuania) and Portugal to less than 4% in Czechia, the Netherlands, and Slovenia.

Against a background of notable minimum wage hikes in the many Member States over the last decade - with statutory rates growing above-average wages in most cases - a growing share of employees fell within the range of statutory minimum wage levels. The proportion of minimum wages earners increased in the EU from 5.5% in 2010 to 7% in 2019.

This expansion occurred especially in those Member States where minimum wage levels progressed the most, notably in central and eastern Europe (Romania, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Slovakia). Significant increases also took place in countries such as Spain, Portugal, and the UK, following notable minimum wage hikes in recent years, as well as in Germany after introducing its statutory minimum wage in 2015.

While this might seem like an increasingly positive picture, further investigation reveals a significant gender divide: more women earn less.

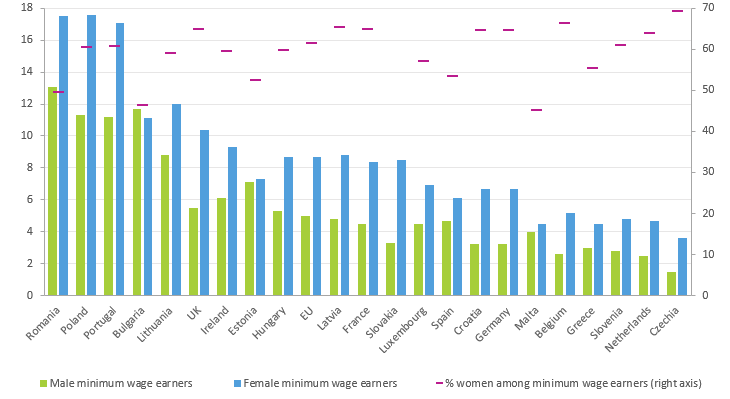

In the EU, there is a higher percentage of minimum wage earners among female employees (8.7%) than among male employees (5%), and women account for over 60% of minimum wage earners. In almost every Member State, more than half of the total number of minimum wage earners are women - in some countries, this rate reaches two-thirds, for example, in Slovakia, Czechia, Belgium, and Latvia (Figure 1). Because they typically make up less than 50% of the workforce, women are significantly overrepresented in this category.

Figure 1: Share of minimum wage earners, by gender and share of women among minimum wage earners (%) (Source: EU-SILC, 2019)

Notes: Countries are ranked by the share of total minimum wage earners, from higher to lower, left to right. Data for Ireland and the UK refer to EU-SILC 2018 wave. The EU aggregate excludes the Member States without statutory minimum wages (not depicted) and refers to the EU-SILC 2018 wave to include Ireland and the UK.

Minimum wage earners are typically found in the lower-paying sectors (hotels, restaurants and catering, retail, health, and other service activities) and occupations (elementary occupations and service and sales workers). This is especially the case for female minimum wage earners since women are more likely to work in these lowest-paid sectors and occupations.

In addition, the education and industry sectors and office-based clerical occupations are other areas where female minimum wage earners may be typically employed. Male minimum wage earners, on the other hand, are often found in industry and manufacturing sectors, as well as in occupations such as craft and trades workers and plant and machine operators.

Minimum wage earners more likely to endure material deprivation

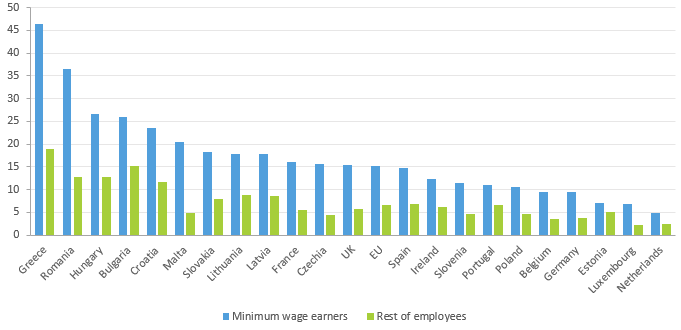

Women are overrepresented in the minimum wage bracket, and minimum wage workers are much more likely to live in materially deprived households. Data show that 15% of minimum wage earners in the EU live in materially deprived households, compared to 6% among the rest of employees (Figure 2).

A household measure of material deprivation captures the capacity of the household to afford several items considered desirable to enjoy adequate living standards, such as being able to pay the rent, keeping the house warm, facing unexpected expenses, going on holidays, and having a washing machine or a telephone.

Across countries, the extent of employees affected by household material deprivation varies greatly: from above 20% in several central and eastern European Member States (Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Croatia), Greece, and Malta, to below 10% in the Benelux countries and Germany.

Figure 2: Share of employees living in materially deprived households (%) (Source: EU-SILC, 2019)

Notes: Countries are ranked by the share of minimum wage earners living in deprived households, from higher to lower, left to right. Data for Ireland and the UK refer to the EU-SILC 2018 wave. The EU aggregate excludes the Member States without statutory minimum wages (not depicted) and refers to the EU-SILC 2018 wave to include Ireland and the UK.

The link between minimum wages and household material deprivation is weakened because the latter is a complex phenomenon caused by multiple factors. Studies have highlighted the joblessness of other household members - rather than low wages - as the main reason for poverty at the household level in Europe. Nevertheless, Eurofound data show that minimum wage earners are much more affected by material deprivation than those employees earning higher wages across all Member States, which reveals a connection between minimum wages and material deprivation. In the current context, it is also important to note that minimum wage earners - and the materially deprived households in which they are more likely to live - are especially vulnerable to economic downturns.

The impact of the pandemic has already taken a disproportionate toll on women across many areas, which is likely to continue. Policymakers need to ensure a comprehensive policy strategy (comprising not only statutory minimum wage rates but, among others, social benefits, income protection, childcare and eldercare facilities, and active labor market policies), improving the working and living conditions of minimum wage earners and their households.

Source: Eurofound